Group Members

Kelly Hammond, Developer/Researcher: Kelly’s responsibilities for this project include automating data collection where possible with Python, researching Newbery award winners, cleaning data for analysis, and creating interactive visualizations of the data in Tableau.

Georgette Keane, Project Manager: Georgette serves as the Project Manager, which includes managing the project and creating a detailed project schedule to ensure completion by the established deadline. She is also responsible for providing support to the other team members, including assisting with data collection and establishing connections with children’s literature professionals and librarians.

Emily Maanum, Designer/User Experience: Emily serves as the Designer/User Experience lead. In conjunction with the Outreach Coordinator, as well as the rest of the team, Emily developed and now maintains the project’s website so it may continue to be useful and informative for the project’s audience. Her other tasks include assisting with data collection and contributing to the project’s outreach.

Meg Williams, Outreach Coordinator: Meg’s main role in the project is outreach. She is responsible for the curation of the blog, the majority of its writing, and the project’s social media strategy. On a conceptual level, she is particularly interested in the importance of minority representation, concepts of whiteness, and the economy of prizes.

Project Narrative

Overview

Diversity and authentic representation matter, especially in children’s literature. As literary scholar Rudine Sims Bishop noted 30 years ago, “When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part.” W.E.B. Du Bois intimated a similar idea in a 1919 edition of the Crisis magazine where he laid out his plan to publish The Brownies Book—a magazine created expressly for children of color—two years before the Newberys were established. Similarly, a study on gender in 20th-century children’s literature points out that “cultural representation, including that in children’s literature, is a key source in reproducing and legitimating gender systems and gender inequality.”

It probably is not surprising that recent studies have shown an overall lack of diversity in children’s books. According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), of the three thousand books published in 2018, fifty percent of books featured a white protagonist, twenty-seven percent of books featured an animal protagonist, and African/African American, Asian Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific American, Latinx, and American Indians/First Nations protagonists completed the remaining twenty-seven percent. While there have been initiatives created by the American Library Association (ALA) and children’s book publishers to address this issue, no full study has been made into the efficacy of these initiatives. To remedy this, we must consider the books children are exposed to and examine the ways in which these books get into their hands.

School and public libraries offer children and their caregivers access to more books than they could purchase for themselves. Libraries also feature carefully curated sub-collections that allow children to locate stories that they relate to and that can help them understand and deal with sensitive topics. More people are going to public libraries each year. According to the 2016 Public Libraries Survey Report by the Institute for Museum and Library Services, more than 171 million registered users visited public libraries over 1.35 billion times in 2016. Even with this increase in patrons, librarians often deal with limited budgets and shelf space, so books must be carefully chosen. Librarians often rely on book lists and reviews for guidance on purchasing, and Newbery and Caldecott Medal and Honor books top these lists. Educators and parents are similarly influenced as they cultivate smaller collections for their classrooms and homes, so even absent a library visit, children are still influenced by these prizes.

First awarded in 1922 to encourage original creative work in the field of books for children, the Newbery Medal is awarded to the author of the “most distinguished contribution to American literature for children” (ALSC). The author must be a citizen or resident of the United States, and the book must be published by an American publisher in the United States in English during the preceding year. First awarded in 1938, the Caldecott Medal was created to honor the artist of the “most distinguished American Picture Book for Children” (ALSC). The artist must be a citizen or resident of the United States, the illustrations must be original works of the artist, and the artist can also be the author of the book. The Newbery and Caldecott Medals are the most distinguished awards presented to children’s books, and studies have shown that after the winners are announced, book sales can increase up to 1,000% (Cockcroft). Book sellers have a vested interest in the significance of the awards and often prominently display these books in shops. The award on the cover drives sales, and the sales reinforce the significance of the award.

Not only is the general public purchasing these books, but so are public and school libraries as well as classroom teachers. Honorees are highlighted on ALA websites and accompanying book lists, and librarians often feature honorees in their display areas and programming. Children become exposed to these works that may or may not help them to understand and handle situations that deal with diversity in religion, race, gender, etc. These books, for better or worse, usually stay on library shelves much longer than other books due to their status as honorees. As one head of children’s services states, “I don’t weed Newbery and Caldecott winners…I feel like if you win the Newbery or Caldecott, you kind of have immortality as a book. I just won’t do it” (Yario).

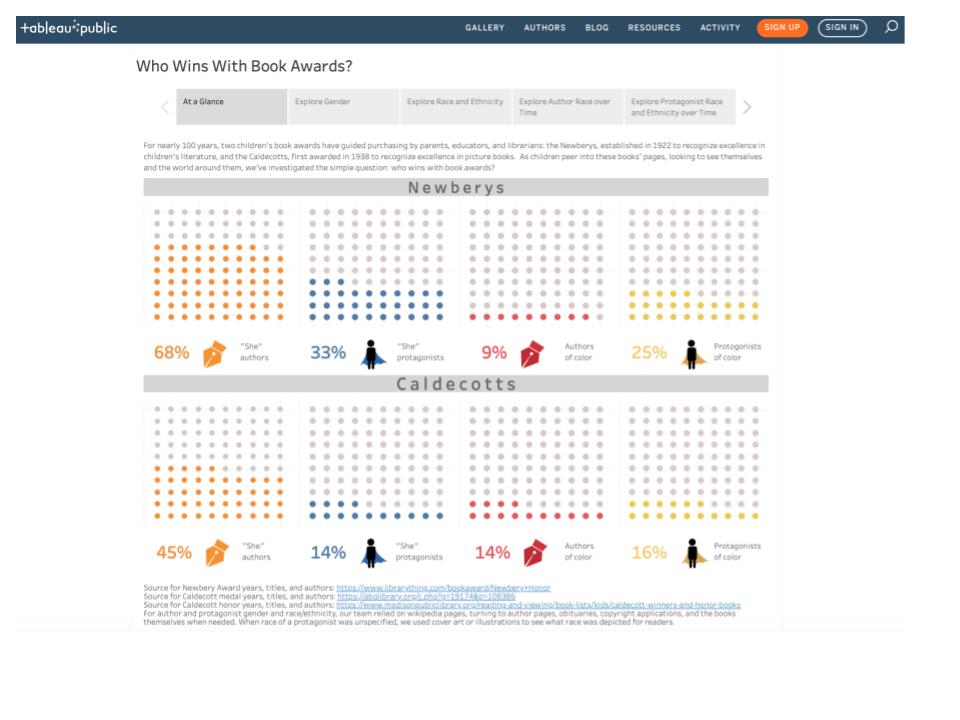

Since the Newbery and Caldecott Medal and Honor Books hold such sway over the public and librarians, we decided to analyze the 763 Newbery and Caldecott ‘Honorees’ (both Medal winners and Honor books) to discover if these books provided an array of diverse backgrounds and whether any diversity was a recent development. We collected the gender and racial/ethnic data of the Honoree authors, illustrators, and protagonists and used Tableau to create visualizations for our audience to explore. We are sharing our findings and recommendations through our website, blog posts, and Twitter.

Our objective with this project is to educate the public on the nature of these prestigious awards. Librarians and educators can use the visualizations to argue for more funding to purchase a wider array of books which fully encompass the experience of their patrons, since our findings reveal that award-winners lack diversity of representation for authors, illustrators, and protagonists. Parents can start to question the primacy of these awards, looking at awardees in more depth and investigating our recommendations for other organizations that promote more inclusive narratives.

Environmental Scan

Who Wins with Book Awards? (WWWBA) is a unique project in the field of children’s literature. Other projects focus on analyzing diversity in the most recent children’s books or create book lists that focus on a particular group or theme. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center releases annual statistics examining diverse authors and protagonists in overall books published the previous year. There are journals—both online and in-print—that investigate diversity, such as the Research on Diversity in Youth Literature (RYDL), a peer-reviewed online journal hosted by St. Catherine University’s Master of Library and Information Science Program and University Library. Librarians, aware of the lack of diversity in literature, will often create public programming to highlight books on diversity or create LibGuides, like Michigan State University Libraries.

The publishing community has recognized the general lack of diversity and has started new initiatives to tackle the issue. Scholastic created the catalog The Power of Story that offers recommendations for books representing diversity of race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and physical and mental abilities. By creating the catalog, Scholastic hopes that young people will have the opportunity to “see themselves and their communities reflected, to read widely, and to understand and expand their world.” Book publisher Lee & Low created The Open Book Blog, a blog on race and diversity in children’s books. Guest contributors discuss current issues and will promote books published by Lee & Low.

In regards to digital projects focusing on diversity in children’s books, the Diverse Book Finder collects information on picture books that feature black and indigenous people and people of color (BIPOC) from 2002 to the present. The themes given on the site are Genre, Categories, Settings, Tribal Affiliation/Homelands, Immigration, Gender, and Race/Culture. An issue with the site is that it only tracks fiction and narrative nonfiction picture books from 2002 and only books with suggested reading levels kindergarten through grade three.

The only digital project found that features diversity and the Newbery and Caldecott Award Books is Lisa Bartle’s Database of Award-Winning Children’s Literature. The database has over 14,000 records from 158 awards worldwide. Bartle, a reference librarian, researches award winners and regularly adds them to the database. Visitors can search by keyword for books or by certain fields like award won or author’s gender.

Although these projects bring awareness to the issue of diversity in children’s literature, WWWBA offers an interactive analysis of all Newbery and Caldecott Honorees. Users can explore the history of the awards and find books that offer diverse content. They can also start to ask questions about the role those awards play in shaping their own (and our country’s) book choices. It is the longitudinal nature of our data that makes our study unique, as we visualize the trends for the last nearly 100 years. For example, we saw that periods such as the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s boasted an uptick in diversity but these periods were often followed by a return to white winners and honorees. We hope to bring other patterns like this to light.

Audience

Our primary audience for this project contains parents, educators, and librarians, as we hope to influence the purchasing decisions that radically shape what books children have access to. We were eager to uncover trends in what are regarded as the most prestigious awards—the Newberys and Caldecotts—hoping to comment on the appropriateness of their hegemony. Our project’s primary purpose is to help purchasers, those gateways to literature, understand the degree to which relying on these awards may limit children’s ability to see themselves in books or to see an array of diverse people or experiences.

By visiting our website and investigating our visualizations, parents, educators, and librarians can re-evaluate the role that the awardees play both in what gets purchased and how long a book stays in circulation, be it on a family’s bookshelf, in the classroom, or at the library. They can also take advantage of two tools we offer for diversifying their collections: tooltips that point them to books whose authors or protagonists have particular identities, as well as a list of other children’s book awards that celebrate more diverse writers and characters. Further, by reading our blog posts, our child-facing audience can deepen their understanding of issues of identity, history, and narrative.

Project Activities:

Project Timeline:

Feb 19th-March 19th:

- Research the ramifications of racial and ethnic categories for authors and protagonists.

- Build Python program to scrape Newbery Honors winners.

- Research author and protagonist gender and race/ethnicity for the Newberys.

- Begin playing with early data in Tableau.

- Draft outline of website: each page (Home, About, Methods, Data, Social Media, Suggested Reading, Infographic), using WordPress through Commons.

- Set up social media and email accounts. RT news on diverse books.

March 20th-April 19th:

- Create Python program to scrape Caldecott Medal and Honor winners.

- Research author and protagonist gender and race/ethnicity for the Caldecotts.

- Combine data sets and create new, interactive visualizations..

- Finalize website design and add to pages; Start blogging.

- Continue RT content on diverse books/child literacy.

April 20th-May 5th:

- Mine the visualizations for content. Continue posting blogs.

- Share revised visualizations and site to test group for feedback.

- Make adjustments to visualizations after initial feedback.

- Reach out to collaborators and audience on social media to announce the published project.

Goals and Adjustments

Our original proposal was to examine diversity in the 415 Newbery Medal and Honor Books. Our work plan consisted of three stages: gathering the data, organizing the data into the pre-approved format, and analyzing the data using the visualization software Tableau. We collected the data using a program we built in Python that scraped the Honorees information from selected websites and generated it into a .csv file. We then cleaned and exported the data to a Google Spreadsheet that the entire team could work in. The data was organized into the following categories: Organization, Award, Year, Title, Author, Author’s Gender, Author’s Race/Ethnicity, Protagonist(s) Gender, Protagonist(s) Race, and Protagonist(s) Ethnicity/Identity. Once cleaned, the data was entered into Tableau to create interactive visualizations.

Gathering the Newbery data took less time than expected, so we expanded the project to include the Caldecott Medal and Honor books. We collected the same data we did for the Newbery Honorees but added the following categories: Illustrator, Illustrator’s Gender, and Illustrator’s Race/Ethnicity. Shortly after our decision, New York shut down due to COVID-19, and we were unable to borrow books from the library. We relied on alternate sources, like YouTube read-alongs and digital newspapers, to find creator and protagonist identities. With these new hurdles, the Caldecott data collection took longer than expected, and as a result, we were unable to share visualizations on our Instagram account prior to public launch. We were active on Twitter, sharing content about the project and diverse creators. As we continue with the project, we will use Instagram to share our visualizations and graphics.

Accomplishments

When starting this project, we wanted to create a product that was useful and understandable to parents, educators, and librarians. Our team’s product consists of a website dedicated to our findings and a Tableau Public workbook that contains our data visualizations. We built our website using WordPress through the CUNY Academic Commons. We wanted to engage our audience with the colorful design found on our site and visualizations. This design uses the vibrant colors that are often found in children’s books.

The website’s home page introduces our audience to the project and provides an overview of the Newbery and Caldecott Book Awards. Under the “About” drop-down menus, users can find our “Meet the Team” page which contains biographies for each of the team members. This menu also brings users to a page containing this white paper and includes a tab linking to a page that contains information on how to get into contact with the team. By clicking on the “Findings” tab, users are brought to a page displaying our data visualizations. Users can interact with our visualizations on this page or click on a hyperlink allowing them to view our data on Tableau Public. Also on our home navigation menu is a “Blog” tab. This tab will bring users to our blog where they can read about issues related to our project as well as our experiences while working on this project during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the right side of our website is a sidebar that lists our recent blog posts and has a scrolling feed of our Twitter account, @whowinsawards. We want to make our recent posts very accessible, and this sidebar feature allows users to click on a blog title that interests them. Our scrolling Twitter feed also shows our audience our recent tweets. By clicking on the feed, users are brought to our Twitter page where they can follow and see what we are up to. The sidebar is not available on our “Findings” page so that it does not interfere with our data visualizations.

As mentioned above, users can examine our data visualizations on our website by clicking on the “Findings” tab. Once there, they can view the data on that page or click the link to view on Tableau Public. Our visualizations are separated into five sections that each go into more depth on several aspects of our data. We put our visuals in “Story” format to make it easier for the viewer to go back and forth between visualizations. Having to continuously scroll up and down can be distracting and may cause some discontinuity between the data. On each slide, users can filter by organization (Newbery, Caldecott or All) as well as by award (Honor, Medal or All). This allows our audience to interact with the data and see how it changes by using different combinations. The colors of the visualizations mirror those found on our website. Users can move through the slides using the arrows on the bottom of our visualizations as well as make the display full screen. They can also share and/or download our findings.

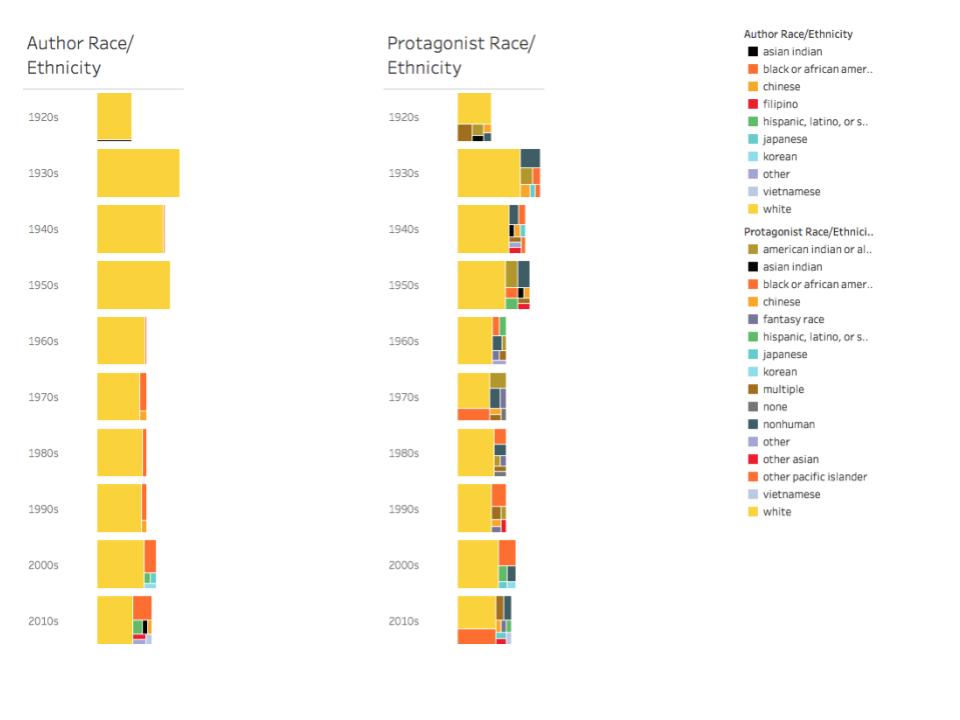

In our Story, the first slide, “At a Glance,” starts by discussing the influence of Newberys and Caldecotts on the purchasing of children’s books, and as the title suggests, gives a brief glimpse into the data regarding authors and protagonists. The next slide, titled “Explore Gender”’ looks at how gender, indicated by “he” and “she” in the books and author bios, compares between awards for both protagonists and authors. “Explore Race and Ethnicity” is the next slide, and it explores the races and ethnicities that are found in these book award winners and honorees. Our next slide continues examining race and ethnicity but looks at these aspects in relation to authors over time. Our final slide, “Explore Protagonist Race and Ethnicity over Time,” gives users the opportunity to explore how protagonist race and ethnicity has changed over the history of these two book awards.

Evaluation

Throughout our project’s development, we sought feedback from fellow digital humanists as well as from members of our intended audience. We started with those associated with our program—Micki Kaufman, Advisor to the Master of Arts in Digital Humanities Program, and Steven Zweibel, Data and Digital Projects Librarian at the Graduate Center. Kaufman encouraged us to consider our data from new angles—to push against the boundaries that informed our visualizations. We followed that advice, creating counterfactual representations, such as those without white authors or protagonists, and investigating the effects of slicing time in different ways, such as looking at diversity by decades rather than individual years.

According to our second round of feedback, the counterfactual representations were not terribly effective, since there was early (though unsustained) recognition of authors and protagonists of color. The view by decades, pictured below, was aesthetically interesting, but feedback from librarians and teachers suggested that the view seemed artificial—that the irregular spacing of eras and movements render regular, ten-year increments less meaningful than less tidy divisions, such as years bookending wars or social movements. Still, that feedback helped us rule out potential paths of inquiry and reinforced the analysis of our initial findings.

Steven Zweibel, as a digital humanist, librarian, and father of a young reader, represents a cross-section of our intended users, and his feedback helped us evaluate how well we spoke to those distinct audiences. He recommended leveraging the power of area to demonstrate our biggest insight—the overwhelming whiteness of award-winning authors and protagonists. We did this with bubble charts on race and ethnicity. Those charts provide the analytical context through which our longitudinal data can be viewed.

Steven Zweibel, as a digital humanist, librarian, and father of a young reader, represents a cross-section of our intended users, and his feedback helped us evaluate how well we spoke to those distinct audiences. He recommended leveraging the power of area to demonstrate our biggest insight—the overwhelming whiteness of award-winning authors and protagonists. We did this with bubble charts on race and ethnicity. Those charts provide the analytical context through which our longitudinal data can be viewed.

We then reached out to a host of parents, educators, librarians, and academics in the field of education. The first wave led us to simplify our view, relying on Tableau’s story format to reduce the length of our Tableau page to more palatable and focused chunks. Subsequent waves helped us tweak language and add clarity. For example, K.T. Horning, director of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center of the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that, since the Caldecott awards are granted to the illustrators of the award-winning books, we may need to include the role along with that of “author.” Most respondents noted that questions generated by the waffle charts were answered in the subsequent slides of the Story, such as how we dealt with nonbinary gender, why we chose the racial and ethnic categories, and what markers were granted to animal and nonhuman protagonists. As Katy Wischow, Senior Staff Developer at Columbia Teachers College Reading and Writing Project put it, “All the things I initially thought to suggest when looking at the project (like how nonbinary/trans authors fit in) you later addressed.” One respondent, a middle-school librarian, asked bluntly where the Jewish authors were, pointing to a layer of data we wanted to include this round but had to save for our expansion, partially because the COVID-19 outbreak kept us from visiting libraries.

Even with this limitation, our research unearthed layers of race and ethnicity beyond the Census categories. Using the 2020 Census lens, white can mean Anglo-Saxon, but it can also mean Middle Eastern, Italian, Irish, Jewish, Swedish, and a host of other heritages and religions. Over the course of the near century of these awards, such degrees of whiteness have, indeed, represented important layers of diversity—groups of people marginalized or rarely reflected in mainstream children’s literature. We opted to save this level of data for our project’s expansion, as it means moving beyond the Census categories—a complicated task we could not complete before public launch.

What was, perhaps, the most gratifying feedback came from 64 independent-school 7th graders from the Chapin School who got to review the data after a virtual presentation from 2020 Newbery Award-winning author Jerry Craft. These 12 and 13-year-olds provided a test of the clarity of our project. Like many digital humanists, we worried that the value of our research might get lost behind the theory. Though we consulted articles, debated about what racial and ethnic categories to use, and investigated the philosophy behind data visualization, we have ultimately designed our work to change minds and spending habits. So, clarity is essential.

These young viewers, unsteeped in societal complexity, asked many of the questions we asked and drew many of the conclusions we drew. Upon seeing the waffle charts, one student said, “Well, it’s cool that most of the Newbery authors have been women, so why aren’t more protagonists female?” Another responded, “I’m not surprised so many authors are women, since society often thinks of them as caretakers. You know, like moms.“ Another replied, “Yeah. It’s the same with the authors of color. First, there are so few. I mean, I thought there wouldn’t be many. But less than 10%? And then look at the protagonists. How real can those stories be if white people are writing them?” Given the conclusions they were able to draw without prompting, our visualizations seemed to be as clear and persuasive as we had hoped.

More importantly, these young reviewers provided suggestions for ways to expand the data. One student asked whether we tracked genre. She wanted to know if “she” authors tended to write a particular kind of book. Another student asked if the relatively balanced ratio of “he” to “she” authors in the Caldecotts had to do with illustration. Since many of those books are illustrated by a person other than the author, she wondered whether those roles break down in interesting ways by gender. Thanks to these curious students, we hope to tackle these new questions in the coming year.

Of course, in addition to outside evaluation, we have also evaluated the project ourselves. We believe that the data and initial line of inquiry have been the strengths of our project. Our findings communicate trends in gender and race in Newbery and Caldecott awards winners. These titles drive sales, launch careers, and shape how children see their place in the world. Going forward, we hope to leverage more fully our website and social media accounts. During the development stage, we devoted the majority of our time to gathering and creating, so we now hope to promote our results through more robust blogging and targeted Tweeting.

Continuation

During Summer 2020, our group plans to continue working on and iterating this project. Our website will continue to be hosted on the CUNY Academic Commons and will be updated periodically with new posts. We hope to add data that will give more context to our visualizations. As noted in the evaluation section, we wish to explore genre and how it intersects with gender, race, and ethnicity in book awards. We would like to make our next-level data, such as author/illustrator roles, visible in edited tooltips and additional visualizations, while we investigate ways to break out of what we consider the distorting structure of the Census categories, where Asian ethnicity is broken up into distinct countries, while continental African identity is lumped with African American. We also hope to expand to other book awards to take a comprehensive look at their diversity.

With a new school year on the horizon, we plan to get more proactive in our social media presence as well; we are eager to push our project (and its summer updates) in the early fall, as teachers set up their classrooms. We believe that some enhanced writing on the website may draw more people into dialogue with our project, and we have already received some interest for conference presentations and a write up for The Horn Book magazine, a journal about children’s literature.

Works Cited

Association for Library Services to Children-ALSC. (n.d.). Caldecott Medal Homepage. http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/caldecottmedal/caldecottmedal

Association for Library Services to Children-ALSC. (n.d.) Newbery Medal Homepage. http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/newberymedal/newberymedal

Bartle, Lisa. Database of Award-Winning Children’s Literature, www.dawcl.com

Bishop, Rudine Sims. “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.” Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom Vol 6, no 3. 1990.

Cockcroft, Marlaina. ‘Caldecott and Newbery Medal Wins Bring Instant Boost to Book Sales’. SLJ, February 10, 2018.

https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=caldecott-newbery-medals-translate-bigger-short-term-sales

Cooperative Children’s Book Center. (n.d.). https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/

Diverse Book Finder. (n.d.). https://diversebookfinder.org/

Du Bois, W.E.B. “The True Brownies.” The Crisis 18. 1919.

The Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2019, May). Public Libraries in the United States Fiscal Year 2016. Washington, DC: The Institute. https://www.imls.gov/publications/public-libraries-united-states-survey-fiscal-year-2016

McCabe, Janice, et al. “Gender in Twentieth-Century Children’s Books: Patterns of Disparity in Titles and Central Characters.” Gender and Society, vol. 25, no. 2, 2011, pp. 197–226. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23044136. Accessed 24 May 2020.

Michigan State University Library, (n.d.). Multicultural and Diverse Children’s Literature LibGuides. http://libguides.lib.msu.edu/c.php?g=96613&p=626684

Research on Diversity in Youth Literature (RDYL) St. Catherine University https://sophia.stkate.edu/rdyl/about.html

Scholastic, Inc. The Power of Story: Diverse Books for All Readers. (n.d.). https://kids.scholastic.com/kids/books/power-of-story/

Yorio, Kara. ‘Librarians Love to Share Award Winners with Kids’ SLJ, February 6, 2018 https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=librarians-love-share-award-winners-kids