This week my primary task was to finish collecting the identity data on Newbery Honor authors and protagonists while Emily tackled the Medal winners—tasks that can’t (or at least shouldn’t) be automated given the sensitive and interpretive nature of determining gender, race, and religion. Unlike the web-scraped details of dates and titles and authors, determining race and gender often included consulting illustrations or original cover art, author websites or obituaries, or reading the first chapter or two of a book.

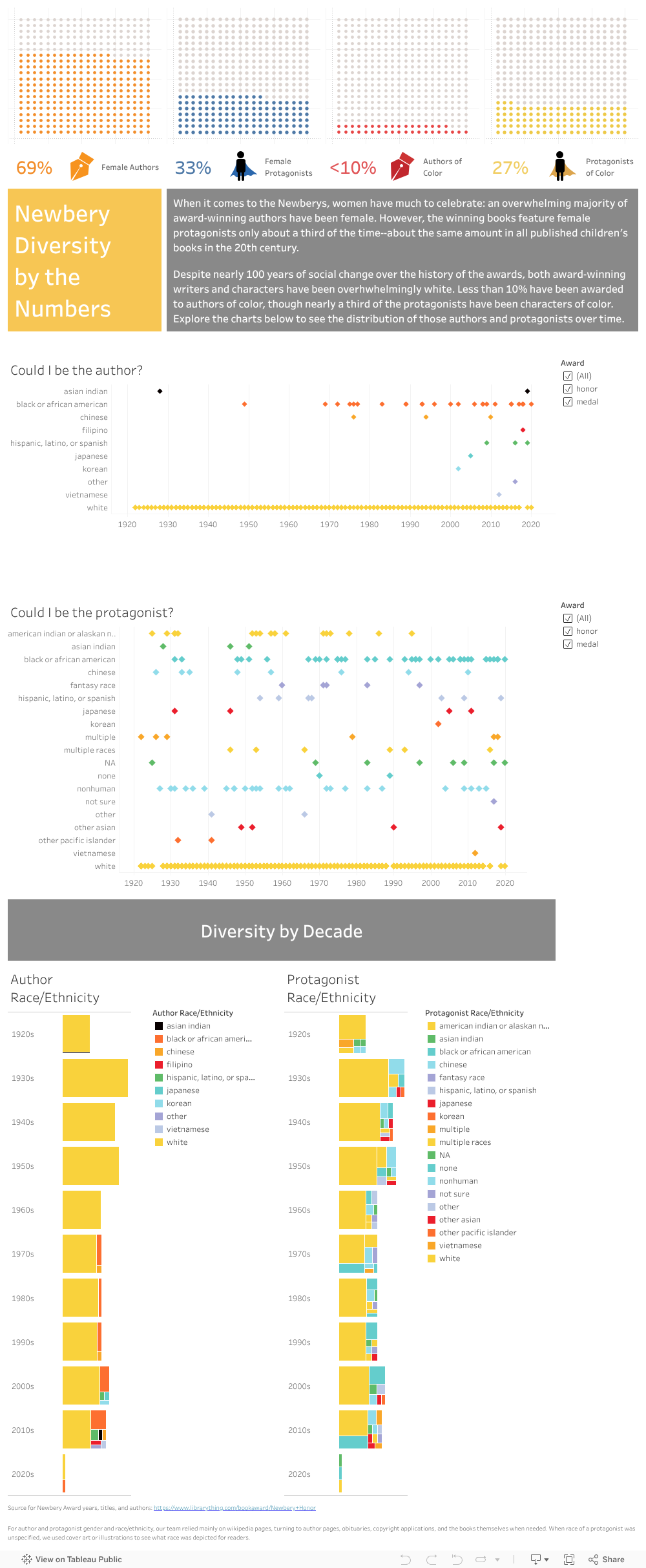

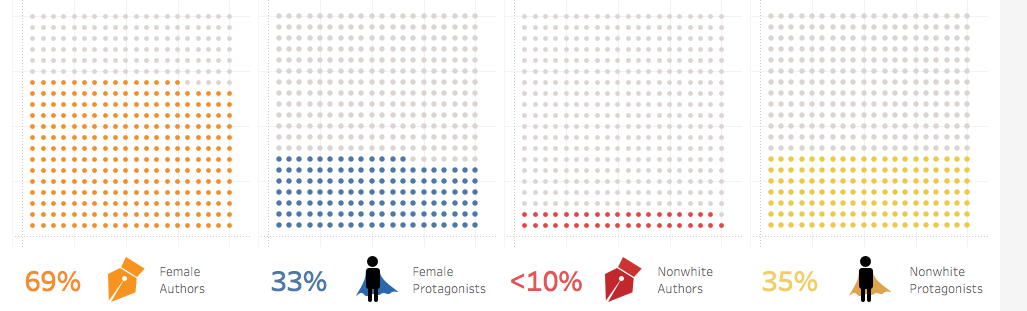

As I gathered details, I also read some articles, both academic and popular, about the categorization of race and ethnicity. The reading highlighted for me that our project is really about whether the Newbery awards, as influential as they are in personal and institutional purchasing decisions and readership, have offered a variety of authors and protagonists in which kids could see themselves in literature. While, in some ways, we entered this project assuming that they didn’t, I found that, as I recorded hundreds of white protagonists and authors, the question of race and ethnicity was more about white versus nonwhite than distinctions of nonwhiteness. What was startling to me (and won’t be to anyone pursuing critical race studies) is that being white in these books or in author bios is often a matter simply of not being something else. Jewish authors were identified as such. Black protagonists, miserably, were often revealed through nonstandard English, African settings, or drug-dealing American neighborhoods. Black writer’s bios touted “the first African American to…” unlike their white counterparts who boasted interests in knitting or meditation or gardening. For the majority of the history of the awards, being white and non-Jewish is, in essence, the default character or author; being anything else is the variation.

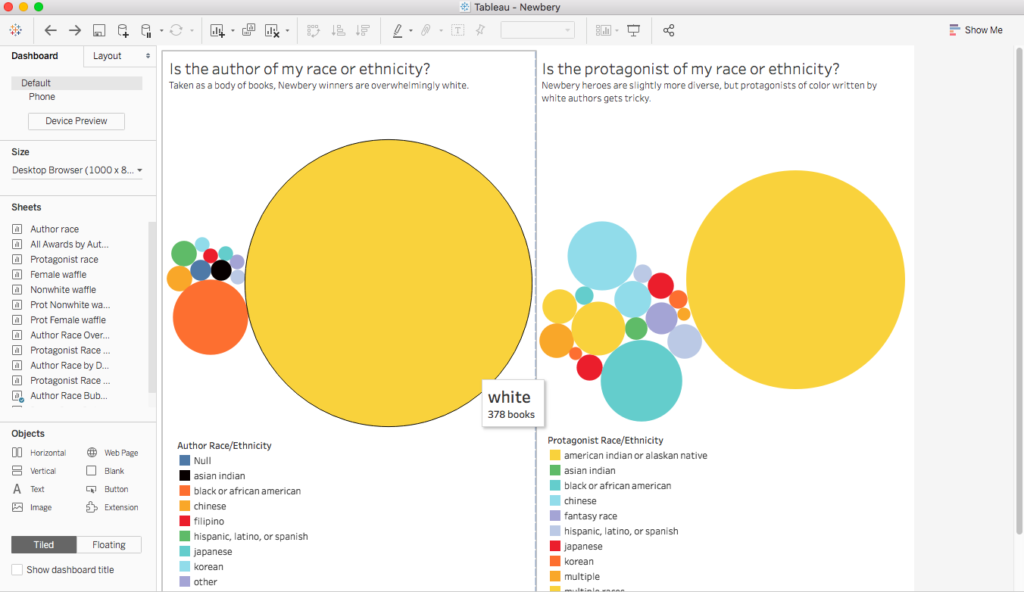

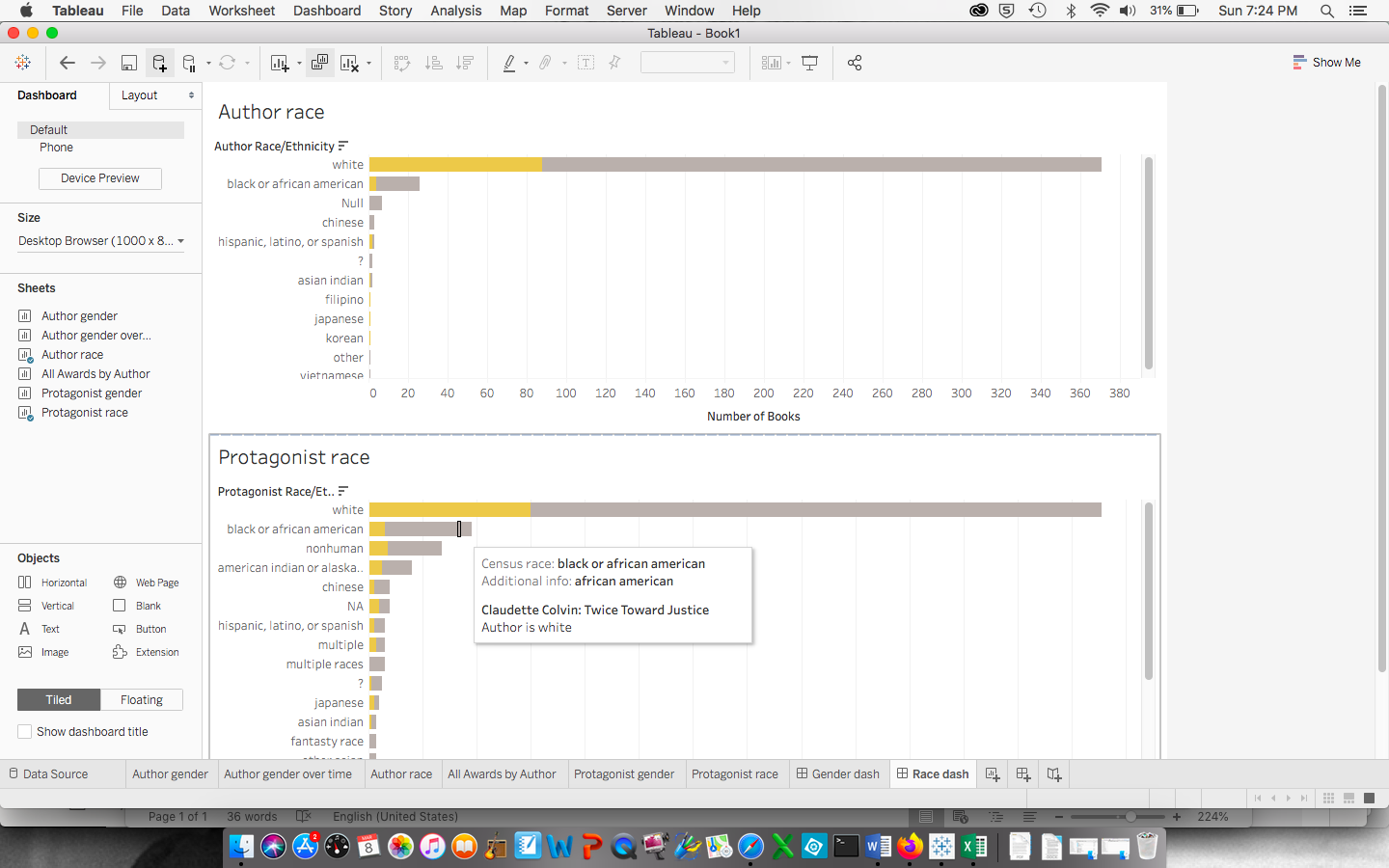

This experience led us to decide that we will play with the data in two ways. Option one is to categorize the authors and protagonists by identifying whiteness and nonwhiteness, with layers of nonwhiteness available to our audience through further exploration with our interactive model. The second is to present the data through the flawed lens of the US Census Bureau, a model that allows us to talk about the slippery concept and powerful, lived realities of the social construction of race.

Some of our research pushed against our expectations. In some cases, Newbery Honorship did not, as we had assumed, guarantee immortality. Some early titles are out of print, and some authors or titles are not yet granted popular regeneration through Wikipedia. By contrast, the system sometimes seems to replicate itself, as the American Library Association, which created the awards, has created new awards in honor of some of its honorees. For example, the ALA granted Laura Ingalls Wilder, who received five Newbery Honors, an award of her own, which many Newbery authors, such as E.B. White and Beverly Cleary, have since received. (Her honor was, in 2018, renamed the Children’s Literature Legacy Award amidst controversy about her depictions of indigenous and black Americans, but until then, it propelled her—a Newbery author—as yet another standard of children’s literature. The renaming might have signaled to the ALA the flaw in their replicated machine.)

One deeply disturbing trend seems clear: Newbery status for diverse books seems sacrosanct for some. Take the case of Jamake Highwater, an honoree boasting Native American heritage who wrote Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey. In the 1980s, Highwater was exposed as a fraud—not indigenous at all—and he lost all federal funding as a result. Yet his book still sells, for $7.98, on Amazon, the cover brandishing its Newbery Honor, despite the wealth of incredibly fine work for kids by indigenous authors such as Joseph Bruchac and Tim Tingle.

While we are still a few days away from our first Tableau experiments with the data, one thing is sure: we’ll want to find ways (perhaps through Tableau’s storyboards or tool tips or perhaps through other sections on the website) to highlight the many unusual stories. Some winning authors are married to or are children of other winners. Some winning stories are about children from countries authors have only visited. Some winning authors share prestigious illustrators, such as Maurice Sendak.

Regardless of our direction in the next month, I realized this week that I wish that our course started with a literature review. I found, midway through this research, a book cataloging Newbery Medalists and Honorees (replete with author and plot info) that I’ll borrow from the CUNY library to double-check our research. Had Emily and I known the book existed, we might have saved ourselves some precious time. A literature review might also have saved us time in terms of deciding racial and ethnic categories in our data ahead of time, which we’ll now have to take time cleaning again.

One issue on my mind for the coming weeks is that of our collaborator’s agreement. The four of us are kind, flexible people, and so far, we’ve been trying to help each other a little more than owning a task and sticking to it. We’ve battled illnesses and tech issues, full time jobs and trips, and while we are making good progress, I’m not sure we’re functioning as leanly as we had anticipated when we first divvied out roles and expectations. We’re torn between wanting to learn all aspects of this project (as we hope to grow as DHers from this project) and wanting to meet weekly project goals to produce something powerful and fine. We’re already on our way to communicating more clearly: we’ve adjusted our weekly meeting time to better suit the group’s schedules. That’s a big step for aw-shucks warm-and-fuzzy people like us.