Abstract

Literacy is essential to a child’s development. Through reading, children expand not just their vocabulary but their understanding of the world around them. But can children really learn from books if a majority of groups and topics are misrepresented or ignored? Recent studies have shown that there is a lack of diversity in children’s books. And while there have been initiatives created to address this issue, the fact that children do not have access to all of these books is something to consider. But what about the books they do have access to?

This project will explore diversity in the most popular children’s literature books, the Newbery Medal and Honor Books. Data collected from the four hundred and fifteen Newbery Books will seek to answer the following questions: Do the Newbery Medal and Honor Books provide an accurate representation of diverse backgrounds and subject matter? If so, has this been a recent development? And are there any trends of note in the honorees? The project team will attempt to answer these questions by collecting the biographical data and subject matter of all four-hundred and fifteen ‘Newbery Honorees’ (both Medal Winners and Honor books), and use Tableau Public to create a digital visualization of their findings and share with the project’s intended audience of librarians, educators and the DH community.

List of Participants

Project Manager/Researcher: Georgette Keane, CUNY Graduate Center

Developer/Researcher: Kelly Hammond, CUNY Graduate Center

Designer/User Experience: Emily Maanum, CUNY Graduate Center

Outreach: Meaghann Williams, CUNY Graduate Center

Narrative

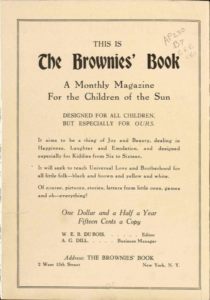

Literacy is essential to a child’s development. Through reading, children expand not just their vocabulary but their understanding of the world around them. But can children use books to expand their understanding of the world if a majority of groups and topics are misrepresented or completely ignored? Recent studies have shown that there is a lack of diversity in children’s books published. In a study performed by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) of three thousand books published in 2018, fifty percent of the books featured a white main character. Twenty-seven percent of books featured an animal, and African/African American, Asian Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific American, Latinx, and American Indians/First Nations were the least represented. Sarah Park Dahlen and David Huyck, who presented these findings in an infographic argue that children’s literature continues to misrepresent underrepresented communities. But their hope is that their findings push conversations about this issue and lead to a change in publishing. And while there have been initiatives created by the American Library Association (ALA) and children’s book publishers to address this issue, the fact that children do not have access to all of these books is something to consider. But what about the books they do have access to?

School and public libraries offer children (and their caregivers) access to a vast number of books that they would never be able to purchase for themselves. Libraries also feature carefully curated sub-collections that allow children to see themselves in a story and can help them understand and deal with difficult topics. And more people are going to public libraries each year. According to the 2016 Public Libraries Survey Report by the Institute for Museum and Library Services, more than 171 million registered users visited public libraries over 1.35 billion times in 2016. Even with this increase in patrons, librarians often deal with limited budgets and shelf space, so books must be carefully chosen. Librarians will often rely on book lists and reviews for guidance on purchasing, and the books usually topping these lists are the Newbery Medal and Honor books.

First awarded in 1922 to encourage original creative work in the field of books for children, the Newbery Medal is awarded to the author of the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. The author must be a citizen or resident of the United States, and the book must be published by an American publisher in the United States in English during the preceding year. The Newbery Medal is the most distinguished award presented to children’s books, and studies have shown that after the winners are announced, book sales can increase up to 1,000%. Not only is the general public purchasing, but so are public and school libraries. Honorees are highlighted on ALA websites and accompanying book lists, and librarians will often feature honorees in their display areas and programming. Children (and their caregivers) become exposed to these works that may or may not help them to understand and handle situations that deal with diversity in religion, race, gender, etc. And these books, for better or worse, usually stay on library shelves much longer than other books due to their status as honorees. As one head of children’s services states, “I don’t weed Newbery and Caldecott winners…I feel like if you win the Newbery or Caldecott, you kind of have immortality as a book. I just won’t do it.”

Since the Newbery Medal and Honor Books are so popular amongst the public and librarians, the questions this project hopes to answer are do these books provide an accurate representation of diverse backgrounds and subject matter? If so, has this been a recent development? And are there any trends of note in the honorees? The project team will attempt to answer these questions by collecting the biographical data and subject matter of all four-hundred and fifteen ‘Newbery Honorees’ (both Medal Winners and Honor books), and use Tableau Public to create a digital visualization of their findings. Hopefully, librarians and educators can use the visualizations to argue for more funding to purchase a wider array of books which fully encompass the experience of their patrons, if in fact, the selections of these awards are found lacking in diversity of representation and subject matter.

The project team will begin by gathering all relevant data from all of the Newbery Honorees. The data will be organized into eight categories: Year; Winner/Honor; Title; Author; Author’s Gender; Author’s Race; Main Character(s); Themes. Half of the data can be found on the ALA’s Newbery Medal Homepage. The researchers will use authors’ and publishers’ websites and the Library of Congress’ and New York Public Library’s bibliographic records to find the author’s gender, race, and a summary of the books and relevant themes. The programmer will experiment with Python to scrape data from these sources where possible. It is important to note that the team will pre-approve the correct format for the data before it is entered into an Excel spreadsheet so as to avoid any errors in the final report. For example, if an author is African-American or Cuban-American, the terms will be entered as ‘African-American’ and ‘Cuban-American.’ In regards to a book’s themes, the team will make sure to use the Library of Congress Subject Headings’ format. If a book’s themes include the relationship between grandparent and child, the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) format is ‘Grandparents and child’ and the theme will be added to the spreadsheet exactly like that. While librarians are familiar with LCSH, other members of the team may not be. The project director will be responsible for instructing the other members about LCSH.

Gathering the data will be the most time consuming part of the project; therefore, the project team will use existing software to display their results. Once the team has organized the data, they will use Tableau Public to create a data visualization of their findings. Tableau Public is a free service that allows users to create and publish data visualizations. Tableau Public users do not need programming experience, and there are many tutorials and a dedicated community available to assist the project team. Published visualizations are available to the public, and can easily be shared through email, social media and on websites. Once the visualization is completed the project team will analyze the findings. Once the visualization is completed, the project team will analyze the findings. The designer and outreach specialist will lead the team in creating a model to share with the public, striving specifically to inform librarians and educators. We also hope to approach the Association for Library Service to Children–the organization who grants the annual award.

Environmental Scan

Finding similar projects has been difficult, as projects tend to focus on analyzing diversity in the most recent children’s books published or creating a book list that focuses on a particular group or theme (gender or race for example). This visualization project will be unique in that it analyzes all four hundred and fifteen Newbery Honorees and that it will be an interactive visualization where users can search for specific information on authors, themes, and main characters. It is important to note these projects because they will provide guidance on how the project team will design the visualizations.

As mentioned above, the lack of diversity in children’s books has been revealed by individuals like Sarah Park Dahlen and David Huyck in their article for the School Library Journal and organizations such as the Cooperative Children’s Book Center. There are journals—both online and in print—that investigate diversity, such as the Research on Diversity in Youth Literature (RYDL), a peer-reviewed online journal hosted by St. Catherine University’s Master of Library and Information Science Program and University Library. Librarians are also aware of the lack of diversity in literature and will often create public programming to highlight books on diversity or create LibGuides, like Michigan State University Libraries.

The publishing community has also recognized the general lack of diversity and has started new initiatives to tackle the issue. Scholastic created the catalog The Power of Story that offers recommendations for books representing diversity of race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and physical and mental abilities. By creating the catalog, Scholastic hopes that young people will have the opportunity to “see themselves and their communities reflected, to read widely, and to understand and expand their world.” Book publisher Lee & Low created The Open Book Blog, a blog on race and diversity in children’s books. The blog will often have guest contributors discussing current issues, as well as promotions of books published by Lee & Low.

In regards to digital projects focusing on diversity in children’s books, the Diverse Book Finder, is a site that collects information on picture books that feature black and indigenous people and people of color (BIPOC) from 2002 to the present. The themes given on the site are Genre; Categories; Settings; Tribal Affiliation/Homelands; Immigration; Gender; and Race/Culture. An issue with the site is that it only tracks fiction and narrative nonfiction picture books from 2002 and only books with suggested reading levels kindergarten through grade three.

The only digital project found that features diversity and the Newbery Award Books is Lisa Bartle’s Database of Award-Winning Children’s Literature. The database has over 14,000 records from 158 awards worldwide. Bartle is a reference librarian and researches award winners and regularly adds them to the database. The page that lists database updates also includes how many of the books Bartle read. As of November 8, 2019, there were 14,397 records in which Bartle read 3,373. Visitors can search by keyword for books or by certain fields like award won or author’s gender.

While there are many people and organizations focusing on the issue of diversity in children’s literature, there is not an interactive data visualization project that focuses on diversity in Newbery Medal and Honor Books.

Work Plan

The project will consist of three stages: gathering the data, organizing the data into the pre-approved format, and then analyzing the data using the visualization software Tableau Public. Gathering the data from the four hundred and fifteen Newbery books will take the longest and involve the entire team. With guidance from the project director, the team will organize the data into the following eight categories: Year; Winner/Honor; Title; Author; Author’s Gender; Author’s Race; Main Character(s); and Themes. The first four categories are available on the ALA’s Newbery site. The team will have to find the author’s gender and race either on the authors’ websites, publishers’ sites, or an internet search (author interviews, etc.). The books’ main characters and themes will be found with the Library of Congress’ and New York Public Library’s bibliographic records. The programmer will expand her understanding of Python to scrape data where possible.

The team will then organize and input the data using a pre-approved format into an Excel spreadsheet. The third stage is to enter all data into Tableau Public, which is a free service that allows users to create and publish data visualizations. The team will experiment with Tableau Public and create visualizations that answer the research questions and share with the project’s intended audience of librarians, educators, DH community, and the Association for Library Service to Children.

Final Product and dissemination

This project will produce a website and digital visualization that explores diversity in the Newbery Medal and Honor Books. The website will outline the issues with other projects investigating diversity, the need for this project, and the overall results. The website and visualization, created with Tableau Public, will be shared throughout the library and information science, education and digital humanities communities. Tableau offers easy sharing of the visualization through social media, web pages, blogs, and emails, so it will be easily accessible to all potential viewers. The hope is that the project will be published in the online publications of the American Library Association (and its subdivisions), peer-reviewed journals hosted by MLS programs like RDYL, and independent publications like the School Library Journal. The project team also plans to submit proposals to conferences like the annual ALA conference and the Association for Library Service to Children’s Midwinter Meetings and/or National Institute, to present their findings.